TRAVELERS India Inc.

Awadh: Reminising About Lucknow and Environs

by Allen Kornmesser, September 13, 2018

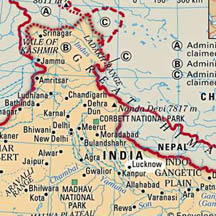

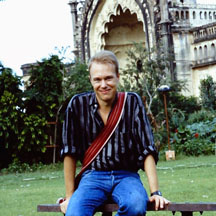

The food of Lucknow, and Awadh generally, is close to my heart. I lived in Lucknow in the late 1980s when I was doing research for my dissertation. I traveled throughout rural Awadh, doing fieldwork in Mankapur (Gonda district), and in Deoria and Gorakhpur at the eastern edge of Awadh.

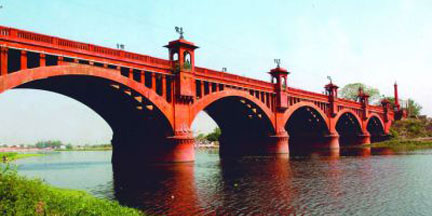

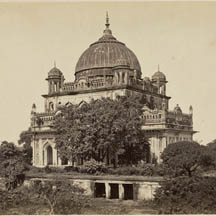

Lucknow has grown a lot since then, but I remember it as a small city with a rich history. Palatial buildings, tombs, mosques, and imambaras dot the urban landscape, fringed by parks and lush gardens, winding narrow lanes, and wide boulevards flanked by shops and government buildings.

The heat was oppressive from May to September, but the city would come alive after sunset, the markets thronged with shoppers, people milling about in the evening air, eating kulfi, or kababs and paranthas, at any of the hundreds of roadside eateries throughout the city. Parties, banquets, concerts, and wedding processions, all waited for sunset. Many of my memories of Lucknow are of the city after dark.

Lucknow is the center of Shia Muslims in India, and flowery and formal Urdu still influences the Awadhi dialect in the city. Poetry lives in Lucknow, and readings attract hundreds and thousands of vocal enthusiasts. Classical music and dance, especially Khatak, are taught and preserved in this culturally rich place.

So, it is fun for me to try and capture some of the spirit of this place I called home for over a year. Our ‘Awadhi Thali’ is a creation inspired by that happy time in my life.

I have been fascinated by the ‘nine-night’ festival of Navratri since my first visit to India. I was aware that Durga was worshipped fervently in Bengal, along with Kali and other goddesses, but it wasn’t until I moved to India for study – I lived in Delhi first, later Lucknow - that I got to see how the festival was celebrated throughout the north of India in cities and villages.

There are two Navratris on the lunar festival calendar, one in the Spring, another in the Fall (technically there is one every lunar month, but only two are widely observed). The dates vary year to year, but they occur near to the equinoxes, as the new moon waxes through the first quarter. The Autumn Navratri is the more widely celebrated of the two, perhaps because it marks the start of the festival season that runs through Diwali and culminates with the full moon of Kartika. The hot weather is ending, and people feel more like celebrating. It also marks a harvest time in the north that gives peasants and farmers leisure time and money to spend on festival activities.

The festival is given an added boost by its coincidence with the Ram-Lila festival which historically has been even more significant in much of the central Gangetic plain, where Lord Ram ruled his kingdom from his capital, Ayodhya, in eastern Uttar Pradesh. Both involve establishing temporary pavilions, or ‘pandals’, where altars are erected to the great goddess to be worshipped in her various forms for nine nights, or where the Ramayana is read and sometimes acted-out over a similar span of time. Both culminate in blow-out festivals on their respective tenth day, Dussahera, or Ram Dashami, with pageantry, fireworks, demons being slain, and virtue triumphing over evil.

Some time in the mid-twentieth century the celebration of Navratri and Durga puja began to spread from Bengal in the east, and Gujarat in the west, to include much more of central north India. In the 1970s I noticed a proliferation of Bengali social clubs in northern cities where Bengalis had large enough populations to warrant them. The clubs would put up the pandals, buy elaborate decorations, including temporary images of Durga and other goddesses and gods, hire a priest, etc., so that Bengalis could enjoy their traditional celebrations wherever they lived. Soon these were drawing many non-Bengalis, and more and more community groups and wealthy individuals began sponsoring pandals in their neighborhoods. Nowadays there seems to be a pan-Indian competition between sponsoring groups to build more and more elaborate and expensive pandals, with more and more exotic themes.

Particularly in the Himalayan region, and probably elsewhere, the public ceremonies also reflect certain social realities and familial relationships. The goddess is treated as a daughter of the community returning to her family home for nine nights. She is a beloved and celebrated guest, and every indulgence is paid her, but at the end of her visit she must leave to return to her husband’s family home. In many places the image of the Goddess is created specifically for the festival, and at its conclusion, after a celebratory send-off, the image is removed to a river and immersed there to float away and be consumed by the elements.

Although it is a time of public celebration and revelry, it is also a very holy time for many devotees, and a time for personal religious activities, worship at home, and fasting. Austerities such as fasting help build a stronger connection to the deity, while also making the body a more suitable vessel for spiritual activities. ‘Tamasik’ foods, particularly meat, but also onions, garlic, and various other foods, are considered antithetical to spiritual practices (they fuel less ’spiritually appropriate’ impulses and behaviors). More ‘sattvik’ foods purify the body, are digestible, such that the body does not pull one away from spiritual practice, and generally elevates one’s state of being appropriate to the ritual activities required of the devotee.

From a culinary perspective, creating a ‘feast’ for a ‘fast’ presents a number of challenges, not least the seeming contradiction in terms. Fasting in Hindu tradition does not necessarily require the elimination of all food, but more often the elimination of certain, often crucial ingredients. Austerities of this sort are thought to produce spiritual merit. For some, only one meal is eaten daily for the duration of Navratri. The rules, like everything in India, vary by region, community, even household, but there are some general rules that are widely observed.

Besides onions and garlic, the fast also proscribes eating grains and lentils – which means no bread, rice, or dal. Beyond that, the restrictions outnumber the allowances. Spices allowed usually include cumin, red chili, black pepper, and cardamom. Fresh ginger and green chilies are okay, and some fresh herbs (cilantro and curry leaf). Salt is okay, but sea salt is discouraged as it is considered more tamasic than ‘purer’ - and ayurvedically more cooling – salt mined from the earth. Salt from certain regions is considered preferable. I am using sendha salt, named for Sindh where it was historically mined.

Otherwise ‘fruits and roots’ are the main foods allowed, although gourds are acceptable as well (pumpkin and bottle gourd/opo/lauki, in particular). Coconut and other tree nuts, and dairy products are okay. None of these ingredients are required. There are also some curiosities that are traditionally eaten during the festival, such as lotus puffs (fox nut), tapioca, water chestnut flour, etc. It’s fun to try to incorporate these into the festival menu. Overall, the thali is tasty, with simple, ‘pure’ flavors, unexpected textures (tapioca and lotus puffs), and a few unusual ingredients. For some Indians it will be a trip down memory lane, for others an opportunity to experience a meal unlike any they have eaten.

Navratri: The Festival and the Fast

by Allen Kornmesser, October, 2018

OCTOBER - Sattvik for Navratri